It’s the beginning of a new school year. The scent of sharpened pencils wafts through the air, and kids are (regretfully) putting the days of summer behind them to return to the grind of school.

This scholastic atmosphere leads me to consider whether higher education helps—or harms—your writing. Is higher education in creative writing (whether undergrad or graduate study) useful? Of course, the answer varies from person to person—some have always dreamed of scribbling away in their dorm rooms; while others have long since graduated and are now considering an MFA (master of fine arts) in creative writing. Either way, it’s useful to weigh your options.

So, in this post, I’ll be considering the pros and cons of higher education in creative writing. Whether you’re considering undergrad of graduate study, I hope this list will be helpful, and maybe even spark some thoughts of your own. So, without further ado, let’s dive in!

Pros

- Mentorship from published authors: this is probably the greatest benefit of schooling—you get to receive feedback and to learn from an experienced writing and teacher. Of course, the quality of mentorship varies from institution to institution, so do your research and find teachers you would want to learn from (try searching for examples of their lectures on YouTube, or look up their writing in your library).

- Peer critique: as in a writing worship, peer critique is a vital part of any creative writing program. You get to refine your own editing skills by finding the flaws in others’ works. Plus, you get a lot of “test readers” who will provide feedback on your story.

- Due dates and deadlines to get you churning out work: this, for me, is key. It’s my number two favorite part of creative writing classes. Let’s face it—it’s hard to stay motivated to write and edit on our own. While meeting deadlines is tough, we get more results for less time as compared with writing on our own.

- Rudimentary business skills: almost any self-respecting creative writing program these days will include a small business component to help you know how to translate your writing knowledge into a marketable resource.

- Help in compiling a portfolio for applying to various creative writing programs (say, an MFA program): your instructor can help you select and polish your best writing, whether for a portfolio or publication. He/she may even be able to provide you with some contacts, as well.

Cons

- Expense: College is not getting any cheaper these days. For all the money you put into college, you might never earn it all back by writing and selling books. Unless you have other sources of income, formal schooling may be an impossibility in today’s economy. (Do note that there are distance learning options for creative writing, which may be more affordable because they eliminate room and board costs.)

- Time commitment: most undergraduate programs require four years of study, and at least half of that may not even be creative writing classes. An MFA program varies from two to three years, depending on how much time you devote to it and the specific courses you take. In contrast, a workshop only requires a commitment of a week or so, at a much lower cost.

- Unrealistic environment: We can’t stay in college our whole lives, even if we wanted to. The concentrated academic and creative environment of college, while inspiring when you’re there, may even harm you once you’re away. If all you did in college was write (unlikely), then you’d be lost in the “real world” without the support system of teachers and peers from college.

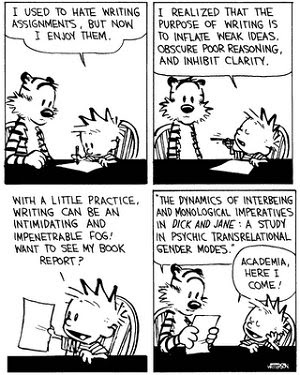

- Literary v. popular fiction: Many creative writing programs teach you to write in a “literary” way, a style of writing that may be beautiful, but might not sell. In other words, you can write books that will sell without going to school for writing. You need to ask yourself, “Is it worth it to learn to write better when I might sell just as many books—or more—the way I write now?”

- Finally, most people can’t earn a living as a writer. Let’s face it: royalties aren’t looking so great. Even ebook sales, while lovely, don’t usually have the mass to support you. Thus, you’ll probably end up working another job. But to work another job, you’ll need a degree other than creative writing. Is it worth it to go to college and get a writing degree when you may not be able to support yourself on it? (Do note that you could also double-major or get a vocational certificate. It’s not black-and-white.)

I hope my points above have been thought-provoking. Now tell me: what benefits and costs do you see of getting a degree in creative writing? Do you have any experience you’d like to share?

Note: If you’re interested in MFA programs, Stanford and University of Iowa are two of the most renowned places to begin your research. Many undergrad schools offer degrees (or minors) in creative writing--use Collegeboard to begin your search.

Image by David Niblack from Imagebase Free Stock Photography